There are whole chapters of US history that most of us have forgotten or haven’t even opened yet—which is unfortunate, because the past is all we have to learn from.

From early 20th century social agitation and progress in workers’ rights (see “The 1911 Triangle Fire, other disasters, and progressive eras,” 5/21/13), we can learn that the 1960’s were not the only progressive era and, in fact, that it could be time for another to begin soon. From the aftermath of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, we learn that horrendous industrial death tolls can force the hands of profit-makers–though not yet, apparently, in Bangladesh, which seems to have just set the world record for factory deaths in one incident (“Killing workers: business and consumption as usual?“).

And from Elaine Brown, we can learn the day-to-day details of what happens when a segment of the population feels so alienated that it tries to take the power it wants into its own hands. Having a shot at power is why many early immigrants came here, and was an old American tradition by the time of the revolution in 1776 and Shays’ Rebellion of 1786-87. The system reacts quickly; the results reverberate for a long time.

Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992) is a testimony of rare frankness about her personal life, surrounded by shootouts, violence against women, violence against men, drug abuse, sex for power, and power for sex.

Before I get launched here, I want to make clear that I am not necessarily approving Brown’s and the Black Panthers’ actions, goals and methods 30+ years ago (which Brown herself renounced). Rather, I am looking into about them as a way of understanding the American past and what paths have led wherever we are going. Some of the issues raised—inequality, racism, violence, the separatist impulse—are old and ongoing ones that all of us should be thinking about.

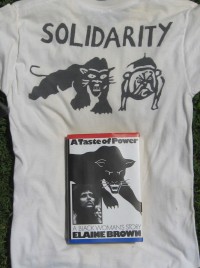

Somewhere, perhaps at my favorite book fair in Harrisonburg VA, I picked up a copy of her book (it’s probably not in your local library, but you can buy it online). The cover image of the iconic black panther snarling or bounding to attack caught my attention because it was prominent in the late 1960s, and I still possess a T-shirt bearing that image, twinned with the Yale bulldog. And the fact that she, like me, was born in 1943 seemed a sign I should add the book to my pile.

There can’t be many of those T-shirts in existence today (image: 1970 T-shirt plus Brown’s 1992 book). I offered it to the Yale museum, but never could get an answer out of them, after the Yale Alumni Magazine ran an article on the Black Panther protests in New Haven: “The Panther and the Bulldog: The Story of May Day 1970″ by Paul Bass ’82 and Doug Rae, July/August 2006. That was less than two years after the assassinations of MLK Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, and after the anti-government movement of the time had dedicated itself to disrupting the 1968 Democratic National Convention, setting in motion the election of Richard Nixon as president and ever bigger abuses of centralized power and covert operations at home and abroad.

Protesters supporting the Black Panthers gathered in New Haven, often staying in students’ rooms, after two Black Panther leaders, Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins, were imprisoned on what seemed to many to be charges invented by the police and/or FBI. “Free Ericka, Free Bobby!” was the rallying cry, compounded by hostility to the war in VietNam, to the US president of the time (who was not impeached for six more long years), and to the Yale president of the time (Kingman Brewster, whose popularity recovered when he was denounced by Vice President Spiro Agnew, who later resigned from office to avoid criminal charges).

Yes, you can see, those were turbulent times.

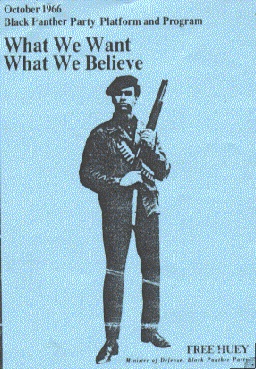

Today, urban black leaders are pleading for gun control but in 1967, according to “BLACK PANTHER PARTY: Pieces of History: 1966 – 1969”:

May 2 Thirty armed Panthers and their supporters go to the California State Capitol at Sacramento to protest the Mulford Act, a bill aimed at banning the display of loaded weapons.

You can bet that if today armed Black Panther paramilitaries occupied street corners, patrolled at night, and had regular stand-offs with police—as was happening in Oakland and other cities where the party had put down roots–a lot of opponents of gun control would have second thoughts.

Brown’s narrative starts right out with the symbolism of the gun, quoting her own aggressive statement to a gathering of hundreds of (mostly male) Panthers where she took over leadership in August, 1974, after Huey Newton’s flight to Cuba:

“I have all the guns and all the money. I can withstand challenge from without and from within. Am I right, Comrade?”

Larry [newly appointed Chief of Staff] snapped back his answer to my rhetorical question: “Right on!” His muscular body tilted slightly as he adjusted the .45 automatic pistol under his jacket…. (p. 3)

Five years before that dramatic moment, Brown “was sent to New Haven to organize a publicity campaign around the impending trial of Bobby and Ericka” (p. 201). She must have carried out the assignment effectively, at the end of 1969, because in May 1970 both the black and university communities turned out to support them. The tear gas flowed freely.

Bobby Seale, then the party chairman, was eventually freed after a jury trial; Ericka Huggins was freed without trial in 1972) and went on to teach Black Studies at Temple University, among other activities. I remember him giving a talk a dozen years ago at Franklin & Marshall College, about his turbulent career as an activist, but what most struck me was his eagerness to sell copies of his 1987 cookbook Barbeque’n with Bobby.

To me, despite all the drama of the Panthers, the most striking part of Brown’s book describes her childhood with a family consisting of three women and a grandfather in the early 1950s not far from Independence Hall in the City of Brotherly Love:

York Street was buried in the heart of the black section of North Philadelphia. Its darkness and its smells of industrial dirt and poverty permeated and overwhelmed everything. There were always piles of trash and garbage in the street that never moved except by force of wind and then only from one side of the street to the other. Overhead utility wires in disrepair ribboned the skyline. Cavernous sewage drains on the street corners spit forth their stench. Soot languished on the concrete walkways, on the steps and sides of the houses, and even in the air. Rusted streetcar tracks from another time, a time when people who were alive occupied the territory, ran up and down York Street. And there was the nighttime quiet. As the dark approached each night, houses were sealed tight in fear and York Street became overwhelmed by the quiet, a silent voodoo drum, presaging nightly danger, a gang fight, a stabbing, a fire. (pp. 18-19)

Even so, somehow the child survived, took classical piano and ballet lessons, excelled in Latin, learned to write as in the excerpt just quoted, wrote and edited Panther publications, and became also a singer and poet.

Her mother had a job pressing newly made clothes (back when American companies made clothes), then worked in a VA office. Her Aunt Mary worked “as a wire clipper on the assembly line at RCA Victor, in Camden” (p. 20, back when such jobs existed). Elaine attended an experimental elementary school, fittingly named after Thaddeus Stevens (you’ve seen him in the Lincoln movie; as a state legislator, he was responsible for saving the once-again-threatened funding of public education in Pennsylvania under the state law of 1834). She got to school by bus and subway, alone, to the Spring Garden stop. In time she went on to junior high and the Philadelphia High School for Girls.

Relief from her neighborhood came from school and also from spending after-school time in the homes of her white, often Jewish, classmates. Ironically, for someone who was to become the leader of the black power revolt, she “became a biddable little wretch” (p. 30) and did her best to become quasi-white. Rejection by and of her father, a prominent black physician, was one step along her way to independence.

After a year at Temple, from which she dwells mostly on her night life, followed by some work as “the first and only Negro service representative at the Philadelphia Electric Company” (hired in response, she writes, to JFK’s demand that corporations begin integrating their employees) at 22 she fled to a new life in California, temporary flirtation with the philosophy of Ayn Rand, waitressing in a strip club, and eventually a relationship with Jay Kennedy, encountered at Frank Sinatra’s house.

The white, married, and mysteriously wealthy Kennedy, who helped (thus along with Bayard Rustin) organize the August 1963 march on Washington, expounded to Brown the virtues of socialism, whereas “Capitalism, Jay said, bred the barbarism of Social Darwinism, wherein only the strong survive and the weak are destroyed” (p. 92). Oddly, however, he also confesses to having worked for the OSS, precursor of the CIA (of this, more later).

In 1967, from a black neighbor, Brown became conscious of the Black Panthers and entered the world of black power militancy. I’m not going to retrace the dramatic events of her next seven years, but they are filled with her interactions with characters like Huey Newton (image from here), Bobby Seale, Eldridge Cleaver, Jean Seberg, Jesse Jackson Sr., Jerry Brown (now, in a striking historical circle, governor of California again), and Angela Davis, and with travels to Moscow, North Korea, North Vietnam, Beijing, and Algeria.

In 1967, from a black neighbor, Brown became conscious of the Black Panthers and entered the world of black power militancy. I’m not going to retrace the dramatic events of her next seven years, but they are filled with her interactions with characters like Huey Newton (image from here), Bobby Seale, Eldridge Cleaver, Jean Seberg, Jesse Jackson Sr., Jerry Brown (now, in a striking historical circle, governor of California again), and Angela Davis, and with travels to Moscow, North Korea, North Vietnam, Beijing, and Algeria.

And there are also her biting assessments of many political figures, such as the Panthers’ enemy number 1:

A postwar anti-Communist paranoia was constructed by J. Edgar Hoover, a friend and manipulator of every president since the 1920’s…. “Freedom” was the watchword. “Free enterprise,” they meant, the men whose monopolies controlled the United States of America, the only interested parties in the business of being number one…. In 1968, Hoover forced a massive augmentation of his COINTELPRO budget and forces. The timing seemed strange since the two men who had embodied for Hoover the only real danger to the internal security of the United States, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, were by then dead. (pp. 234-238)

Rather surprisingly, the Panthers turned to electoral politics in 1972, with Bobby Seale and Elaine Brown running for Oakland City Council (unsuccessfully). The Panthers backed Jerry’s Brown’s presidential campaign in 1978; Elaine Brown was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention and played a major role in the election of Lionel Wilson as Mayor of Oakland.

Then, having finally had enough of the sexism, violence, and drugs around her, she departed, with her small daughter, for Los Angeles, leaving the Panthers behind and moving toward the lengthy process of writing the book.

In some ways, the book reveals an alternative history that could have happened: the Panthers could have become a third-party political force; Brown and Seale could have won seats on city Council; their ally of the time, Jerry Brown, now as then governor of the nation’s most populous state, could have become president; their enemy J. Edgar Hoover could have been disgraced as Senator Joe McCarthy had been. But, as usual, the system won out.

The book serves as testimony to the period from the 1950’s to 1978, when racism remained more overt but in some circles (including in Philadelphia and California) relations between the races were surprisingly fluid.

As a personal story, it spares nothing. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his Confessions, said he set out to show himself entirely as he was. In my view, Brown comes a lot closer.

The Wikipedia entry on her dwells at some length on the later discovery that Jay Kennedy had spied on MLK and was spying on the civil rights movement as a CIA agent during the time of his affair with Brown. Whether he learned anything of use to J. Edgar is unclear; rather, his influence on Brown may have made her a more effective leader.

That the CIA, forbidden from spying on Americans, was doing just that, in concert with the FBI, comes as no surprise to anyone who lived through the 1960s or has witnessed the ongoing domestic surveillance programs from then to this day.

PS The April 29 issue of The New Yorker, p. 76, briefly reviews Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party by Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr.:

By 1970, the Black Panther Party had grown from a small group in Oakland, focussed on “armed self-defense against the police,” into an international political organization pursuing a “global anti-imperialist struggle”….

As of June 27: for a much longer review, see “Rage and Ruin: On the Black Panthers,” The Nation, June 24/July 1 2013, by Steve Wasserman, who was part of the Panther movement himself.

Pingback: Elaine Brown and the Black Panther movement | progressivenetwork

Pingback: “The Butler”: an unexpected history of race relations in America | politicswestchesterview

youtube.com/watch?v=8Mb8VJ_C9UI

assata-shakur.blogspot.com/2010/07/geronimo-ji-jaga-says-that-elaine-brown.html

In her book, A Taste of Power (page 167 on) Brown admits she was TRAINED and PAID and sent into the Party by Jay Richard Kennedy, the informant in Dr. King’s inner circle for the CIA Security Research Section (birth name: Richard Solomonick).

Jay Richard Kennedy was a former Bureau of Narcotics, OSS man who was also the manager for Harry Belafonte, until Belafonte FIRED him in the 1950s.

JRK was a partner in the Mafia-owned Sands Hotel in Vegas, which is where Elaine Brown met him while working as a hooker in ’63 (her own admission, see her book).

JRK was the owner of a factory in Quebec that produced proximity fuses for the US military during the VietNam war, and (like the UK’s Ian Fleming) the author of numerous spy books from ‘the inside’ of the agency, such as “Man Called X” and his bestselling his book / movie ‘The Chairman’.

JRK was the one who postulated to SRS that Dr. King was a tool of Mao and laid the groundwork for the premise that allowed his assassination.

His ‘confession’ can be found in the British documentary ‘The Men who killed Martin Luther King’.

More information can be found in David Garrow’s book ‘The FBI and Martin Luther King’.

Mr. Pratt,

Have you ever heard that Manson-clan victim Gary Hinman may have had some kind of relationship with the BPP?